Taberner House is being demolished.

You might think that Croydon town centre is overrun with landmarks. There are, after all, over forty office blocks jostling for attention. But few of them are instantly recognisable from a distance. There's the spectacular Thrupenny Bit, of course. The rugged Nestle building. The awkward twins Lunar and Apollo House. But Taberner House was always the most handsome, the sharpest suited, the king mod in his tapering Italian styling.

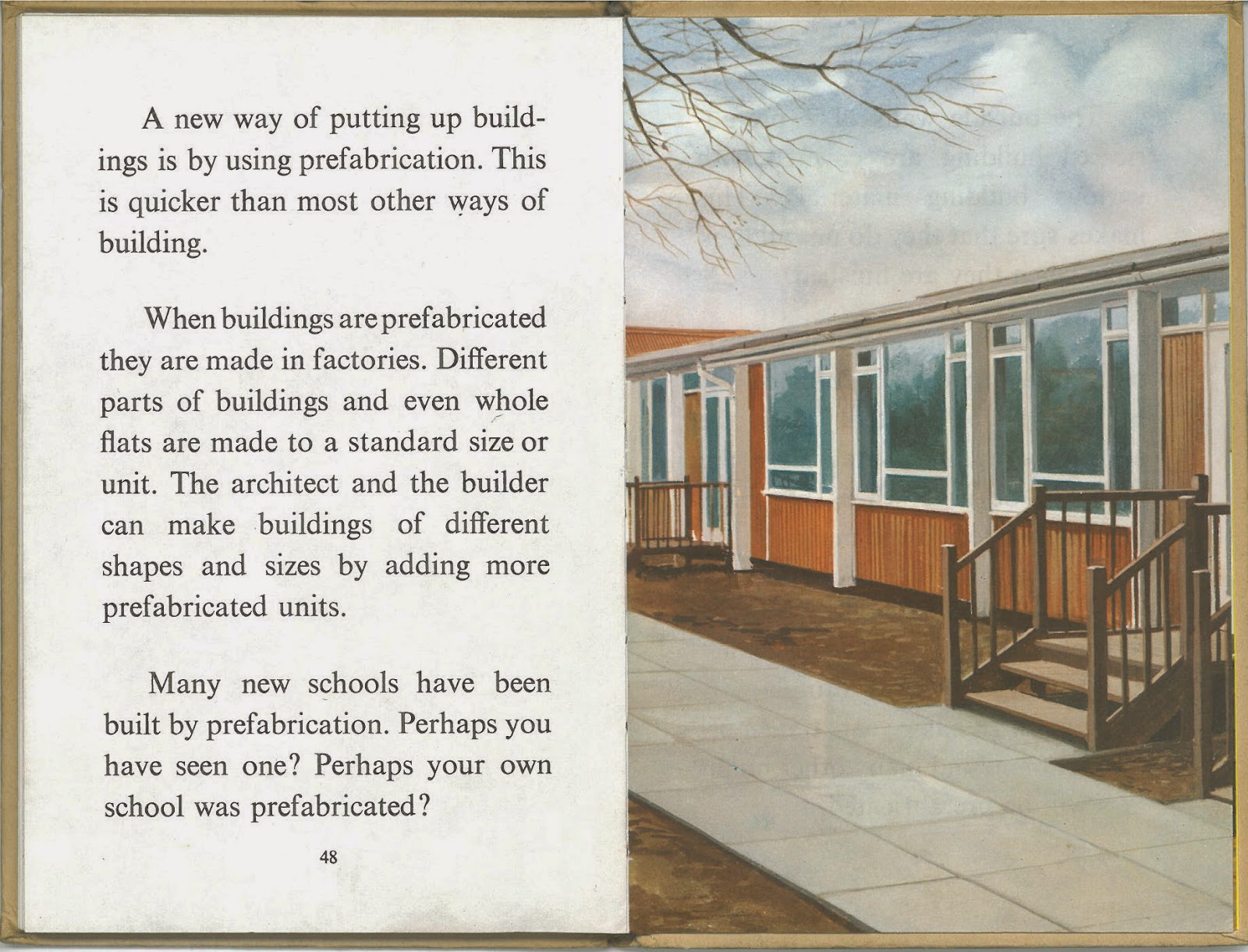

![]() |

| (c) Stephen Richards |

Taberner House was the council office from 1968 to 2013. 45 years. Just think of all the admin generated on typewriters and notepads in its nineteen storeys over the years. The memos sent between floors in the internal mail. The filing cabinets heaving with manila folders, dockets and Roneoed forms. Those glass walls would have seen the arrival of the modern office: first the word processors and green-screen computers, the dot matrix printers and fax machines with their fancy thermal paper; devices taken over in their turn by the PC and the laptop, tablet and smart phone. No more telegrams to Whitehall or calls patched through from the mechanical switchboard. Now the windows are being taken out, the building stripped and dismantled floor by floor. Architect H. Thornley will find the monumental building he designed is about to disappear into the murk of history, just as he has.

But for me, there’s a strange personal story here too, a ghost of the official one, a bit-part player's view of the proceedings. Taberner House represents something brief but remarkable in the life of my parents.

![]() |

| My Mum and Dad in the late 70s | |

|

In the 1970s, when I was very small, my mum was depressed. Fiercely clever, Marjorie Grindrod had, like many women of her generation, been greatly disappointed by her life in a suburban council estate, miles from her large extended family. All apart from one of her brothers, Bert, who lived in the maisonette upstairs but never spoke to us. But that's another story. She was looking after us three boys, and my dad was out working all hours for little money as a lorry mechanic. She was also coping with something more debilitating. In the 1960s she'd had a series of operations to remove cycts from her spine. She'd recovered, but the surgery had left her with a pronounced stoop, and she found herself occasionally dependent on a wheelchair.

When things did begin to change for her, at first they got very bad indeed. In 1981 she was afflicted with intense, sudden and unexplained internal bleeding. All of her family came to visit her, and everyone was certain she would die. But she didn't. When she left Mayday Hospital ten weeks later, she instead snapped back into the world more alert, more interested, more impressed with life than she had been in all the years since I had been born. It was incredible to see. She came out of hospital a different woman – a stronger, more determined, more optimistic one.

Physically the illness had left its mark: a lack of physiotherapy while she'd been in the hospital bed for all of those weeks had a terrible effect on her legs. She was never able to walk again. And so she continued her recovery at Waylands, a day centre for people with disabilities. This modest centre in Waddon encouraged people to take up activities such as pottery and painting. I still use the lamp she made, a beautiful tree that sits on my bedside table. But in a matter of weeks she was bored with crafts, and instead found herself teaching other people to type and write letters. It was clear that she'd begun to remember a previous life, one before children, before marriage: the time in the early sixties when she was working as a PA for the director of the department store Arding and Hobbs in Clapham. With all of the skills she was remembering, and her new zest for life, within a year she went from near death to an invaluable volunteer. She took a place on the board of the local Dial-a-Ride, and in no time at all she took over chairing it in her typically no-nonsense way. For the next couple of decades my mum became one of the great and the good, a volunteer who set up a community transport scheme and helped plan the Tramlink.

And she spent a lot of time in Taberner House. Mainly, she would remind me, as a fire hazard. Such were the health and safety procedures and evacuation rules in event of a fire she was, basically, in the way. We were going to make a sticker for her wheelchair that said Fire Hazard, to officially recognise her status. Despite this, meetings were always held high up in the building. Often my dad, John, would go along too as official wheelchair pusher, until she finally relented and got an electric wheelchair. At least twice a month she’d be there, stuck in long meetings, sometimes taking minutes, sometimes chairing them, always looking out at the high rise landscape of Central Croydon from that incredible height. And so her visits to Taberner House began to feel like a symbol of her recovery, not just from the illness, but from the depression that had crushed her in the seventies. It was for her a happy place, and somewhere she'd often come back from with another nugget of absurd overheard conversation. Council employees in the lifts, people who thought they were hidden safely behind partitions, workers striding down corridors, none of them were safe from my mum's radar for stupid remarks.

My dad also had a one of his legendarily great moments in Taberner House. There was a level of expectation wherever my dad went that he would do something so utterly stupid that it would entirely redefine what people thought was possible there. He certainly didn't disappoint. This happened long after he'd given up his job as a lorry mechanic following a heart bypass operation. He'd worked instead at Waylands, the day centre who had rescued my mum, and where he'd instantly become the most loved man in the building. If my mum was cool, ironic and lightning quick, dad was a soppy teddy bear of man, always up for a bit of Norman Wisdom-style physical humour. But by the late nineties, he was ill again. This time it was cancer. He'd recently had to retire from his job, which everyone was very sad about. And so he was still invited to work outings. Waylands staff had their Christmas do at the top of Taberner House. This particular year it was fancy dress. Dad had been all over the place with his illness, and wasn't sure he could make it. On the day he felt well enough to go, though he hadn’t managed to arrange a costume. So imagine his delight on arriving to the top floor of the council's offices to discover an outrageous leopard-print dress just lying around. Perfect. He quickly changed into it, and entered the party in improvised drag. It caused a sensation. This was because it immediately transpired that he was wearing the dress that one of his former colleagues had changed out of only moments before, when she’d got into her costume. She was amazing about it, and told him that he looked much better in it tan she had, and I think he was secretly rather chuffed.

![]()

Writing about them like this it sounds as if my parents were always full of illness, endlessly in hospital, always about to die of something or other. When they both did actually die, my mum in 1998, my dad in 2000, it was a huge shock. If you get used to people recovering from life-threatening illnesses for your entire life, you no longer fear that they will actually succumb to one some day. Actually, that's bullshit. I was so used to thinking about death all the time back then that I had constant panic attacks and at least once a day used to think I was having a heart attack. Because it has to all be about me. But of course it wasn't. They had real illnesses, ones there was no way back from. And they are long, long gone, which is very odd, because when I think about them, which is all the time, it's as if we had only just finished chatting a moment before.

So when great lumps of the world they moved in are removed, great lumps like Taberner House, it really means nothing in the grand scheme of things. Next to the death of a loved one it is as inconsequential as a sneeze. But even so, it is a strange sensation, seeing that great tower being stripped and broken down. I've tried to talk about my parents and Taberner House in the same breath. It is an absurd notion. All of the modern architecture in the world could be knocked down if it meant that... Yes, well, you get the idea. It is almost impossible to see anything else after staring into the sun like that.

Still, Taberner House is being demolished. The space my mum and dad once occupied, as fire hazard and improvised drag act, will soon be a void in the air a hundred metres above the Croydon flyover. The very fabric they once inhabited has gone. The place occupied by many hundreds of people over those 45 years, with all their memories and routines, has gone. It was just an office block, a piece of clapped out Italian-style modernism from another era. And when it's finally stripped right down to ground level we can all look up and see the ghosts of those filing cabinets and gestetners, plug-boards and wire trays, suspended high in the air above the centre of Croydon, with nothing to support them now but blog posts and elegies.