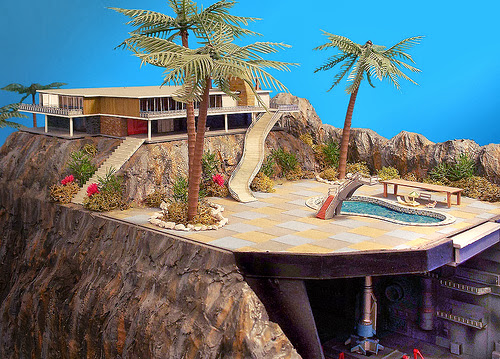

'Top People' is one of those chirpy Carry On-era Rank Look at Life documentaries made for the cinema. This one is all about the rebuilding of the City of London, 1960. It centres around Great Arthur House, the tower block at the heart of the Golden Lane estate which sits just beyond the City's boundary. It was this massive and successful design job that ensured that architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon would get to create the City's largest housing project next door, the Barbican, a model of which can be seen in the film, as well as the blitzed land on which it was to be built.

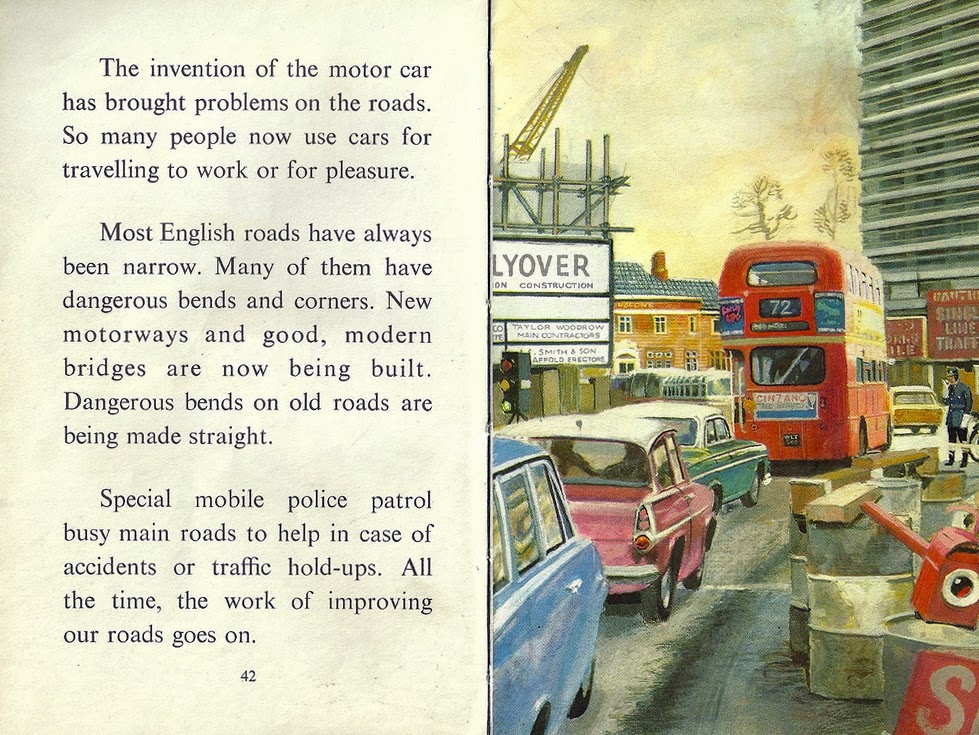

The film gets its thrills not from the architecture, but from the daredevil feats carried out every day by its builders. Shots of the scaffolder's feet standing on the end of a scaffold pole hundreds of feet above the ground, mixed with shots of him blithely standing there with no safety harness of any sort, are guaranteed to make my feet cringe even now. Similarly the window cleaner shinning off a balcony on a rope and clambering over to a balcony some feet away makes me feel a bit ill.

The Barbican site was hit hard by industrial action throughout the sixties. The received view of the British worker, even then, was of a tea and beer-loving skiver, who was only too happy to picket if it didn't mean working. This film does a surprisingly good job of shocking us into remembering how tough and basic the conditions were for builders on these massive projects, and how little interest there was in safety. It's a reminder of how the modern world was build in an always shockingly old fashioned way.

Despite the cheesy window cleaner cuppa set up at the top of Great Arthur House this is a pretty tame affair by Look At Life standards: no leering Sid James narrating, for example, or cutaways to 'pretty girls'. So it feels a little more like a straight piece of social history and less like a cheap shot at the subject. Well worth a watch.

The film gets its thrills not from the architecture, but from the daredevil feats carried out every day by its builders. Shots of the scaffolder's feet standing on the end of a scaffold pole hundreds of feet above the ground, mixed with shots of him blithely standing there with no safety harness of any sort, are guaranteed to make my feet cringe even now. Similarly the window cleaner shinning off a balcony on a rope and clambering over to a balcony some feet away makes me feel a bit ill.

The Barbican site was hit hard by industrial action throughout the sixties. The received view of the British worker, even then, was of a tea and beer-loving skiver, who was only too happy to picket if it didn't mean working. This film does a surprisingly good job of shocking us into remembering how tough and basic the conditions were for builders on these massive projects, and how little interest there was in safety. It's a reminder of how the modern world was build in an always shockingly old fashioned way.

Despite the cheesy window cleaner cuppa set up at the top of Great Arthur House this is a pretty tame affair by Look At Life standards: no leering Sid James narrating, for example, or cutaways to 'pretty girls'. So it feels a little more like a straight piece of social history and less like a cheap shot at the subject. Well worth a watch.