It will come as no surprise to anyone who's read

Concretopia that I am a fan of first person interviews with people who have created or lived in postwar buildings. The fashion is much more towards the visual: to record buildings on Instagram, for example, rather than to investigate what it was built for or what life is like for the tenants. Not that I have anything against that, of course, I love looking at pctures of architecture as much as the next geek. But I've been pleased to see a couple of recent publications bucking that trend – using visual media to tell the story of the people and the place, rather than simply recording its coolness, or otherwise.

The first was Robert Clayton's book

Estate, about the Lion Farm Estate, where he'd recorded the lived of residents back in some midlands council flats in the early nineties. And now, just published, is another more extensive art project, by the artist Stephen Willats.

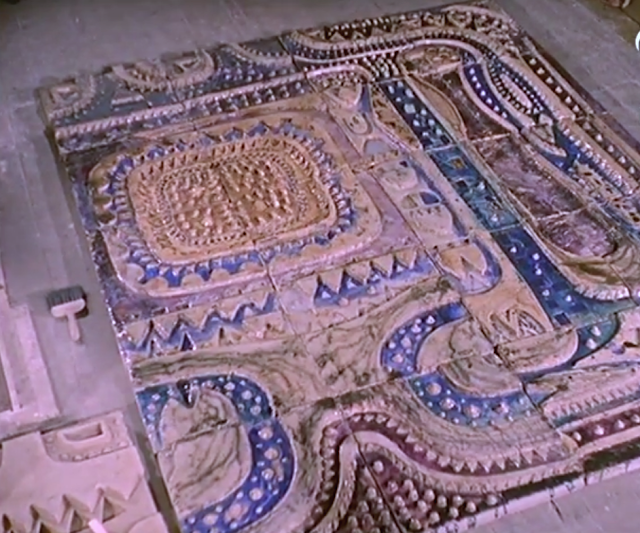

Vision and Reality collects together 22 different projects by the artist, carried out in different estates round the country between 1974 and 2008. Published by the excellent

Uniformbooks,

Vision and Reality takes the form of photographs and interviews with residents, and each chapter opens with one of Willat's artworks, collages with text, photos and graphics to show the interrelationship between the residents and the way they live in their environment.

The results are fascinating and touching, and remind me slightly of Tony Parker's wonderful classic work of oral history

The People of Providence, about a Wandsworth housing estate in the early eighties. Here the photos of people and their possessions are presented in a flat documentary style, and the interviews and observations also follow very similar patterns across the decades. And so there are pictures of remote controls, model sailing ships, cookers, televisions, electric fires, nests of tables, ornaments, dartboards and net curtains, beside pictures of residents of all different backgrounds and ages. The responses to the landscape and furnishing of the residents in the accompanying interviews are often hugely insightful and from unexpected angles, entirely disabusing anyone who might wish to dismiss the experience of people in social housing as similar or predictable.

![]()

![]()

I'd really recommend reading this book if you're into the social history or art of postwar British council housing. One thing I do worry about with the book, though, is from the title, cover and blurb it is very difficult to know what you're getting. I think there's potentially a much bigger readership for this book than the rather enigmatic presentation might allow. Don't let that put you off, though. Here's a list of the estates recorded in the book:

Skeffington Court, Hayes, Middlesex;

Friars Wharf Estate, Oxford;

Ocean Estate, Mile End, East London;

Brandon Estate, Walworth, South London;

Charville Lane Estate, Hayes, Middlesex;

Avondale Estate, Hayes, Middlesex;

Queen Caroline Estate, Hammersmith, West London;

Tottenham Hale Estate, North London;

Brentford Towers, Hounslow, Middlesex;

Sandridge Court, Finsbury Park, North London;

Dobson Point, Newham, East London;

Farrell House, Whitechapel, East London;

Marlborough Towers, Leeds;

Lovell Park Towers, Leeds;

Homecourt, Feltham, Middlesex;

Warwick Estate, Paddington, West London;

Saffron Court, Snow Hill, Bath;

Linacre Court, Hammersmith, West London;

Kelson House & Topmast Point, Isle of Dogs, East London;

Heston Farm Estate, Hounslow, Middlesex;

North Peckham Estate, South London;

Coffee Hall Estate, Milton Keynes.

Vision and Reality by Stephen Willats, published by Uniformbooks, 2016, £18 Paperback